Managing Anger and Aggression in Young Athletes

A Coach's Guide to Violence Prevention

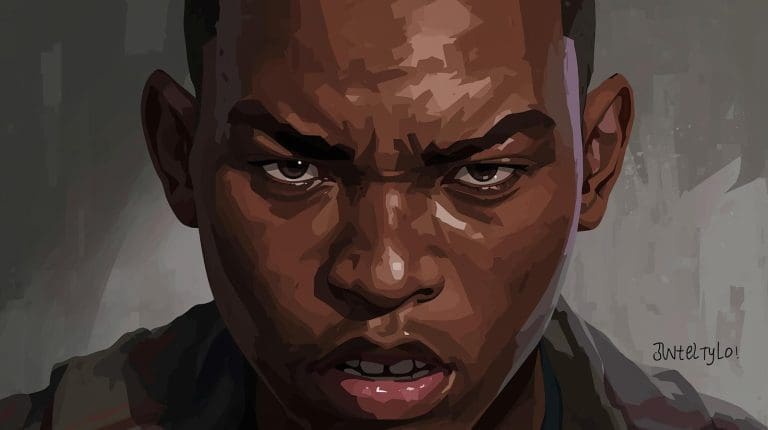

When a talented 21-year-old striker receives a provocative challenge during a crucial match, their response in that split-second can define not just the game’s outcome, but potentially their entire sporting career. John H. Kerr’s compelling examination of anger-based aggression in sport, published in the Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, offers coaches invaluable insights into understanding and managing these critical moments with young athletes.

Understanding the Violent Incident

He uses the infamous 2014 Rugby League Grand Final incident involving Ben Flower as a case study that resonates across all contact sports. Within just two minutes of the match, Flower’s violent retaliation to a provocative strike resulted in his sending off, severely disadvantaging his team and culminating in their loss. For coaches working with young athletes aged 17-21+, this scenario isn’t just about rugby, it’s a cautionary tale applicable to football, hockey, basketball, and any competitive environment where emotions run high.

What makes Flower’s case particularly instructive is the convergence of factors that contributed to the incident: intense rivalry, media pressure, high arousal levels, skill frustration, and direct provocation. These same elements exist in youth sports, where young developing athletes face immense pressure whilst still learning emotional regulation skills.

Why Young Athletes Struggle with Anger Management

The adolescent and young adult brain is still developing, particularly in areas responsible for impulse control and emotional regulation. Coaches must recognise that teenaged and young adult athletes are navigating:

- Performance pressure from coaches, parents, scouts, and themselves

- Identity formation where sporting success feels intertwined with self-worth

- Peer dynamics and the desire to appear tough or dominant

- Hormonal influences affecting mood and reactivity

- Limited experience in managing high-stakes competitive stress

Understanding anger-based aggression through Kerr’s framework helps coaches distinguish between sanctioned aggression (hard but legal physical contact within the rules) and unsanctioned violence (actions that cross ethical and regulatory boundaries). This distinction is crucial. Ideally young athletes would be competitive and physically committed, not passive, but never violent.

Recognising the Four Types of Aggression

Kerr’s categorisation helps coaches identify problematic patterns:

- Play aggression (sanctioned): Competitive physical contact within the rules

- Power aggression (unsanctioned): Intimidation tactics to dominate opponents

- Anger aggression (unsanctioned): Retaliatory violence following provocation

- Thrill aggression (unsanctioned): Violence for excitement or to provoke reactions

For coaches, recognising which type an athlete defaults to is the first step toward intervention. The young striker who consistently uses late tackles to intimidate requires different support than the athlete who occasionally loses control when provoked.

Five Evidence-Based Strategies for Coaches

- Build Genuine Trust and Communication

Establish an environment where young athletes feel safe discussing emotional challenges without judgement so that they become good at changing how they think about difficulties. This authenticity creates space for honest dialogue about anger triggers.

- Help Athletes Identify Their Triggers

Work with individual young athletes to recognise the specific situations, opponents, or circumstances that provoke their anger. Is it:

- Verbal taunting about family or background?

- Physical intimidation tactics?

- Perceived injustice from referees?

- Frustration when skills don’t execute as planned?

- Feeling disrespected by opponents or teammates?

Encourage athletes to notice their bodily sensations when anger builds. Does tension affect them? Does their heart rate increase? Are they feeling tunnel vision? This can help them intervene before losing control.

- Develop Personalised Anger Management Techniques

Different athletes require different approaches. Kerr’s article suggests two main pathways:

Arousal reduction techniques: For athletes who benefit from calming down, teach progressive muscle relaxation, controlled breathing, or brief visualisation exercises. The key is making these accessible during competitions and matches. A three-breath reset during a break in play, for instance may work.

Cognitive reframing: Help athletes reinterpret provocative actions. Instead of viewing an opponent’s physical play as disrespect requiring retaliation, reframe it as an opportunity to demonstrate superior skill and composure. Transform “They’re trying to hurt me” into “They fear my ability.” And where they become good at asking themselves “great” questions in the moment, such as “how can I be calm and seek to dominate them legally?”

- Use Cue Words and Pre-Competition Routines

Work with athletes to develop personal cue words simple phrases that remind them of their commitment to controlled aggression. “Composed power,” “ice cold,” or “channel it” can become anchors. These work best when practised repeatedly in training and at home, not just introduced before matches.

- Proactive Rather Than Reactive Intervention

Don’t wait for incidents to occur. Integrate anger management into regular training:

- Create scenarios in practice where athletes experience frustration or provocation

- Role-play appropriate responses to common triggers

- Celebrate examples of emotional regulation as much as goals or wins

- Discuss high-profile incidents like Flower’s case as learning opportunities

When Anger Becomes Dangerous

Coaches must recognise when anger-based aggression crosses into territory requiring professional psychological intervention. Warning signs include:

- Repeated violent incidents despite interventions

- Anger extending beyond sport into personal relationships

- Physical intimidation of teammates or coaches

- Inability to discuss emotions without becoming defensive or hostile

- Expressions of violent fantasies or extreme revenge thoughts

In these cases, refer the athlete to a qualified sport psychologist or mental health professional.

Practical Implementation

Start small. Select one or two athletes who struggle with anger management and implement these strategies consistently over several weeks. Document what works and what doesn’t. Share successes with your coaching community, effective anger management strategies benefit everyone across youth sports.

Remember Ben Flower’s reflection: “The hype of the whole week blew up in one overreaction from me.” Arguably the role of a coaches is to help young athletes navigate that hype, manage the pressure, and channel their competitive fire into performances they’ll be proud of, not incidents that can go on to haunt their careers.

Why not join our online community – THE SPORTS PSYCHOLOGY HUB – for regular Sports Psychology tips, podcasts, motivation and support.

Best Wishes

David Charlton

Global Sports Psychologist who is located near Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK and willing to travel Internationally. David also uses online video conferencing software (Zoom, Facetime, WhatsApp) on a regular basis and has clients who he has supported in the UK, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Australia and New Zealand.

Managing Director – Inspiring Sporting Excellence and Founder of The Sports Psychology Hub. With over 15 years experience supporting athletes, coaches, parents and teams to achieve their goals, quickly.